We have problems. God can help. God wants to help.

We want Him to help! And we figure we know just how he ought to go about doing so.

God, however, seldom dances to our tune.

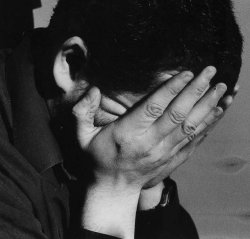

Job had problems. His problems were epic, legendary. He wanted—desperately—God’s deliverance.

Job’s three friends were of little help. God eventually rebuked them, saying, “you have not spoken of me what is right” (42:7).

Once they’d shot their counseling-wad a fourth figure steps to the fore and offers his take on Job, his problems and how he’d been responding to them. Elihu is a somewhat enigmatic figure. Just how are we to view his contribution to this drama? He is unlike Job’s three friends in that they each shared in three rounds of debate with the sufferer, allowing Job to respond after each round (Job 4-31). Not so with Elihu. He offers four discourses aimed at Job and his response to suffering (Job 32-37). There is no response from Job. When Elihu steps down from the mic, neither does God make a response to him or what he’d said. God simply turned to Job and responded to him and what he’d said (Job 38-41). Its almost like Elihu didn’t exist and his speech was inconsequential!

So how are we to understand Elihu and what he said? I can’t satisfactorily answer that weighty matter here. Perhaps in some way he prepares for Job to hear God when he eventually breaks the heavenly silence.

One point Elihu makes is one I think we all need to hear. Sometimes God delivers us, not by removing our adversity, but by sending it. Perhaps God’s willingness to appear at least temporarily passive or disinterested with regard to our affliction is the greatest proof of his commitment to be our perfect Deliverer.

“He delivers the afflicted by their affliction and opens their ear by adversity” (Job 36:15; cf. also 33:19-22).

Perhaps the very thing we feel need of being delivered from is the means of the real deliverance we desperately need. What we feel need of deliverance from actually may not be our greatest need.

The words picture a person “afflicted.” The affliction is not specified, but in context we ought to picture Job. We’re not talking inconveniences here; this is deep affliction. He needs to be delivered, but by what means? Who will do so? And how with it happen?

Elihu reminds us that it is “by their [very] affliction” that deliverance comes. This can only mean that my perceived (and, indeed, real) affliction is not my only or even primary affliction.

Every sufferer has another, deeper problem than the one stealing their attention. The lesser affliction is sent to rescue from the greater affliction.

Just how is it to do so? It does so because it “opens their ear.” It gets their attention. It opens their awareness. There is a willingness now to listen to God, where perhaps there had not been. The sufferer will now consider possibilities that were heretofore brushed aside.

Isn’t this what C.S. Lewis was getting at in The Problem of Pain? He asserted that “God whispers to us in your pleasures, speaks to us in our conscience, but shouts to us in our pains: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.”

Dr. Paul Brand who spent a lifetime dealing with the numbing and destructive effects of leprosy in undeveloped countries of the world said, “If I had to summarize the grand design of pain in one phrase it would be this: Pain is directional. It hurts not in order to cause discomfort, but to demand a change in response to danger” (In His Image, p.258).

So perhaps I need to revisit my feelings. Maybe I need to open my ears and shut my mouth. Could it be that God is willing to risk temporarily being thought unkind or unjust in order to prove that he is ultimately and eternally compassionate and merciful?

Lord, just what is it you are saying to me? Help me hear! Amen.